Jun 4, 2024 Written By Yashi Davalos

To look at today’s infrastructural development through the American capitalist lens is to recognize how it embraces simplified aesthetics to depict visions of a white future. Modern art, too, often employs minimalism to look forward at the expense of rich storytelling. Standing in stark opposition to this style of art is Salvador Jiménez-Flores, who incorporates Rasquachismo, the Chicano practice of reusing and repurposing, to envision a new kind of future—one that centers Black and brown perspectives. In Arte-Sano: Soy libre porque pienso at the Belger Crane Yard Gallery in Kansas City, MO, the Mexican artist uses transmigratory world-building and nonlinear expressions to dismantle reductive perceptions of Latinx art and explore the politics of identity.

Through his art, Jiménez-Flores examines how musicality, generational relationships to craftsmanship, and iconography have shaped industrialization and migratory patterns. He began forming this point of view across several residencies including the Kohler Arts Industry, Watershed Center for the Ceramic Arts, and Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, among others. Each residency lets the artist investigate culture through time and labor while strengthening their practice. For example, Jiménez-Flores’s work with clay reflects the pre-Columbian assimilation of working with the earth and his family’s legacy of farming; his work with metal at Kohler considers industrial labor.

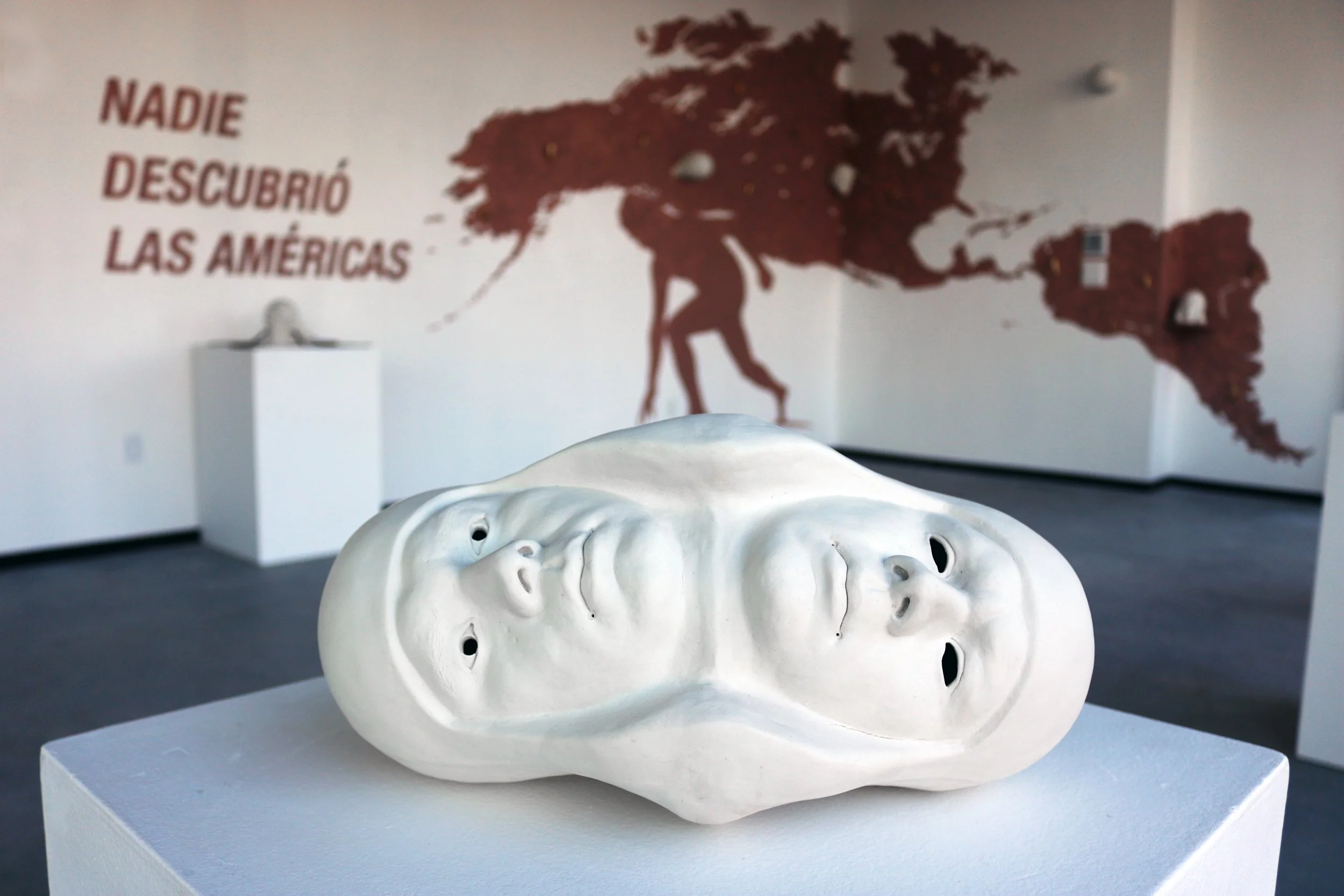

In the gallery, there are two bronze emergences: one that appears to sprout from a pedestal and the other from a moving wall. Titled El surgimiento de una nueva realidad (The Rise of a New Reality) the bronze cast mimicries of Jiménez-Flores’s head are set against tribal markings on the wall and pedestal—the separation representing a fragmented voyage. In many aspects, the neo-Columbian tribal markings reflect the different identities one must adopt through migration, as is the case with his family who moved back and forth between the United States and Mexico.

Salvador’s great-grandfather first arrived in the Midwest in the 1900s for railroad construction, starting the family’s relationship to the area as a traquero. Decades later, his father would migrate through the Bracero Program, which invited Mexican nationals to come to the U.S. from the 1940s to 1960s for temporary agricultural work. His father eventually made his way back to Chicago in search of job stability but later, in the 1980s, the family returned to Mexico, where Salvador was born. At 15, Jiménez-Flores rejoined his family members who had once again found themselves in Chicago.

With Arte-Sano, Jiménez-Flores depicts identity through a shared consciousness and collective, generational stories. For example, in the Árbol de vida series, he merges terracotta, black stain, glaze, wax, and gold luster to represent the conditions Black and brown communities endured in the Little Village area of South Side Chicago—a place currently feeling the effects of environmental racism.

The messages in the pieces are clear: “We can’t breathe,” “Aire limpio,” “Hell no to Hilco,” the latter referencing the company that, in 2020, irresponsibly handled the implosion of a coal power plant. Jiménez-Flores’s powerful words suggest that one cannot thrive in toxic environments and the best way to resist and fight is to come together as a community. The verticality of the sculptures symbolizes the artist’s commentary on disrupting this social hierarchy through narrative.

On top of challenging storytelling methods, Jiménez-Flores’s self-portrait sculptures resist traditional concepts of time by juxtaposing elements of Afrofuturism and Rasquache Futurism—two theories that examine labor and time in nonlinear ways.

Sun Ra, recognized as the father of Afro-futurism, influenced the concept through space music being a tool to combat infrastructural time. Similarly, this exhibition’s title is a nod to a Calle 13 song, “Yo Soy Libre Porque Pienso,” in which Residente, a.k.a René Pérez Joglar, speaks of how society pushes for assimilation, which leaves him feeling mentally subdued. Instead, the rappero claims that self-liberation is possible by filling your time as you wish, even sitting through boredom, in contrast with work, which adheres to strict schedules and depletes us in the process.

It is this relationship to time that influences the layout of this exhibition and how you experience Jiménez-Flores’s work. You are free to explore the work from any point—a remark on how identity and migration intersect without a fixed beginning or end.

In another section of the exhibition, a trio of clay sculptures appear horizontally. Titled I Am Not Who You Think I Am, this series includes an industrialesque assemblage of the El Milagro tortillas logo and Jiménez-Flores’s head, a split cast of Mexican Revolution figure Emiliano Zapata, and a depiction of Native American phenotype.

This portraiture addresses the intersectionality between imaging uninterrupted Indigenous futures—that is, those without imperial colonial intervention—and the idea of migration as resistance. This surrealist impression of what one might classify as pre-Columbian art challenges the concept of linear time for Americans who accept the chronological interpretation of art history.

Jiménez-Flores’s relationship to Sun Ra is apparent in his use of fire. Within the Monuments and Memorial series, fire appears to be ceremonial. The memorial aspect also speaks to being of the land and rising from the ashes, suggesting rebirth. Tracing the manipulation of American emblems within the gallery, the transformation of symbols within the context of Rasquache Futurism presents the clash between industrial labor and land expansion. The ceramics mimicking the American eagle also represent the United States’s national bird but also represent the land before the Louisiana Purchase.

With antenna-like features on their heads, the eagles embody both the U.S. and Mexico and their shared history and future. Seemingly from another dimension, the eagle sculptures of the Kitschy Americana series are at the center of the exhibition, once again breaking away with conceptions of linear time.

Through various manipulations, Jiménez-Flores shows that meritocracy has no linear reference because the narratives of laborers only receive praise in fragments, which means we miss out on the full truth. Jiménez-Flores’s practice waves a thread through different timelines to explore intersectional narratives of migration. This signals that growth under Rasquache Futurism is about continuously reclaiming time, so we can continue to reshape our understanding of the truth.

Yashi Davalos (Yashira Lopez Davalos) b.1995, is an artist, writer, and independent curator. Her upbringing as an Afro-Latine, Atlanta native mobilizes her objective to build artistic dialogue critiquing non-monolithic aspects of identity. Yashi is currently the curatorial fellow at The Charlotte Street Foundation in Kansas City where she currently lives and works. Davalos’ writing has been featured in Burnaway and Sixty Inches from Center. Her art has also been exhibited throughout New Orleans, at Plug Gallery in KCMO, Mint Gallery ATL, and In Partnership with Elevate ATL for Atlanta Art Week.

https://www.latinxproject.nyu.edu/intervenxions/salvador-jimenez-flores